This year the summary of Kherson’s media year will be more subjective than usual. The author distributed the key events of the year into categories, however, that does not mean that nothing else happened to Kherson media professionals. So much happened that it will require writing three, or maybe five, long pieces. We’ll leave that for the memoirs of Kherson journalists, and for now let’s look at a few important trends of the year.

Word of the year: “kill zone”

Some still mistakenly believe that Kherson lives in a gray zone, but since the summer of 2024 the city has become a real “kill zone,” where people play hide-and-seek with death every day. Although local journalists prefer not to call Kherson that, in reality their lives and work in the city have long turned into that kind of hide-and-seek.

“A report that almost cost me my life (mom, sorry you’ll find out from Facebook)”, – wrote in October Kherson journalist Valentyna Pestushko. She and a press officer had to stop filming a story in the Korabel neighborhood after a Russian FPV drone appeared in the sky.

“In the middle of the shoot we were warned about high drone activity, and after some time we heard the familiar buzzing approaching our direction. Alive thanks to luck and the high professional skills of the accompanying press officer. Shooting had to be stopped for several hours. Despite that, the material was filmed and published”, – she later told. This is not an isolated case and every media worker working in Kherson can tell a dozen such stories, but most of them do not want to worry their mothers.

Obviously, almost every media worker in Kherson has a drone detector, without which going to work is now unthinkable, and their own safety rules. Some know the hours of lower Russian drone activity, some plan routes along “safe” streets. Also in 2025 almost all media workers in the city abandoned PRESS stickers.

“In Kherson, breaking the rules, you can’t mark yourself as press, because I myself have repeatedly been in situations when drones that were supposed to fly past you start searching because they saw the inscription or photo equipment. I have more than once hidden under trees. At one point I even began to pray, because it hovered over me for so long”, – he told IMI in September Oleksandr Kornyakov.

It should be noted that during the filming of that material the media workers nearly got hit by artillery shelling. Despite having to work under such conditions, Kherson media continue to produce reports and news from the city daily. And none of them during this time has said they are doing something heroic. Just work. Just in the “kill zone”.

Value of the year: trust

Kherson journalists often talked about trust last year too, but this year that value gained during the war capitalized even more. Increasingly, journalists from different newsrooms worked together on topics, shared insider information, victories, and losses. And it seems that this is what allowed most of them to work even better.

We mentioned trust when we analyzed this year the state of political and commercial paid content in the media. The critically low percentage of materials with signs of commissioned content found by our monitoring on the one hand pleased, and on the other forced reflection, including among colleagues. It is obvious that the war destroyed the market for “black” information services. After the occupation of part of the region, evacuations, business losses and the destruction of political structures, those who financed hidden political advertising disappeared as well. Former clients – local politicians, businessmen or party headquarters – either left or lost any influence.

In the new conditions, paying for a good story became pointless: independent media survive not because of deals, but thanks to the trust of their audience.

It should not be forgotten that Kherson journalists also went through a complete reevaluation of the role of their profession. During the occupation they became literally the eyes and voice of the city – a source of information on which people’s lives depended. After such an experience it is difficult to return to old practices when a publication was determined not by public interest but by money. In most local newsrooms ethics is now not a chapter in a manual, but part of self-identity.

“Audience trust has become a new currency. In a region that experienced occupation, the media became a symbol of resistance. Therefore any sign of commissioned content is perceived painfully – it immediately hits reputation. Readers distinguish truth from PR, and this explains the high bar of standards that local journalists have set for themselves. I won’t say that there are no cases when media praise politicians or, conversely, ‘trash’ them, but that is so rare, and it is mostly practiced by gutter sites that only mimic being media”, – says reporter Petro Kobernyk of the publication “IRS-South”.

Challenge of the year: USAID

For independent media in Kherson region, both large and very small newsrooms, the closure of USAID programs in Ukraine became a critical challenge for many. However, no media outlet in Kherson region closed due to the loss of donor funds from the USA. Moreover, large newsrooms managed not only to avoid staff cuts, but even to increase them.

“Overall the situation at the end of the year looks much better than at its start. During the year we won a number of grant competitions from European donors and began working with new partners we had not cooperated with before. This provided a sense of support and allowed us to ensure continuity of work. At the same time, the current situation is difficult to compare with the development opportunities media had a year ago. Due to the constant search for funding we had to postpone a significant part of our strategic tasks that we planned to implement in 2025”, – says Ilona Korotitsyna, director of the media Vhoru.

Approximately the same situation is with other media in the region. MOST, for example, also had to focus in the spring on finding funding sources instead of strengthening content production.

It must be said that it was somewhat easier for large and well-known regional media to find funding, because donors knew them, they had production capacities and established staffs and could take on obligations in more or less large content grant competitions.

“We, as a small media outlet, were probably not interesting to big donors. Several of our own applications that journalists from IRS-South submitted to competitions were not supported. Although one donor helped us buy equipment, which was very useful”, – said media head Petro Kobernyk.

According to him, the lack of stable funding greatly complicated fieldwork. Trips to communities and to the military require significant expenses. “We tried to find money from other sources, reallocated funds from those projects we managed to find, and could continue to travel around the region and film. Not as much as we would like, but we did not stop doing it”, – he said.

Media also sought other sources of income. MOST, for example, opened its small production unit, which allowed it to earn the first one hundred thousand by providing filming and video editing services.

Vhoru decided to develop a community and an advertising department.

“This year showed how important it is for media to develop different monetization paths and reduce dependence on donor support. Throughout the year we tried to show our readers the conditions in which we work and how important their support is. Thanks to this, subscriptions and reader donations gradually increased. Advertising revenues did not grow significantly. An internal challenge was finding a second sales manager due to the specifics of working in a regional frontline media. However the main thing is — we restructured our work and can confidently say that we have come out of the financial crisis. We have effectively stopped operating in survival mode and can focus on development and strategic goals”, – shared Ilona Korotitsyna, director of Vhoru.

Project of the year: Antidote

For the fourth month now listeners of Kherson’s Radio X.ON have been hearing weekly jingles from the project “Antidote”. Radio host Kateryna Tsymbalyuk and correspondent of the “Center for Journalistic Investigations” Petro Kobernyk weekly, live on air, talk about Russian propaganda fakes related to Kherson region and debunk them.

In more than ten episodes of the program Kateryna and Petro have debunked dozens of Russian fakes about Kherson region that were aimed at residents of the temporarily occupied by Russia part of the region (TOT) and people in the territory controlled by Ukraine.

The aim of the disinformation spread among TOT Kherson region residents is to discredit, dehumanize and demonize Ukraine, to form the image of it as “neo-Nazi.” Disinformation aimed at residents of the right-bank part of Kherson region deoccupied in 2022 is spread to create an atmosphere of fear, uncertainty about the future and, most importantly, mistrust of Ukraine.

Kateryna Tsymbalyuk says that the idea of a project to debunk Russian propaganda fakes had been in the air for a long time, and Kherson journalists pushed the radio hosts to implement the idea by “infecting” them with the conviction that such a program was necessary for Kherson region.

The program is a volunteer project without funding. “We are heard not only on the right bank, but also on the left, in the TOT. So the idea had to be implemented. We all see what is happening on social networks, what the feedback is, what people fall for, how they emotionally react. We just need to help them cope with this informational onslaught. We call it supporting information hygiene, supporting your informational health. Like any health, it requires care and some professional advice”, – says Kateryna.

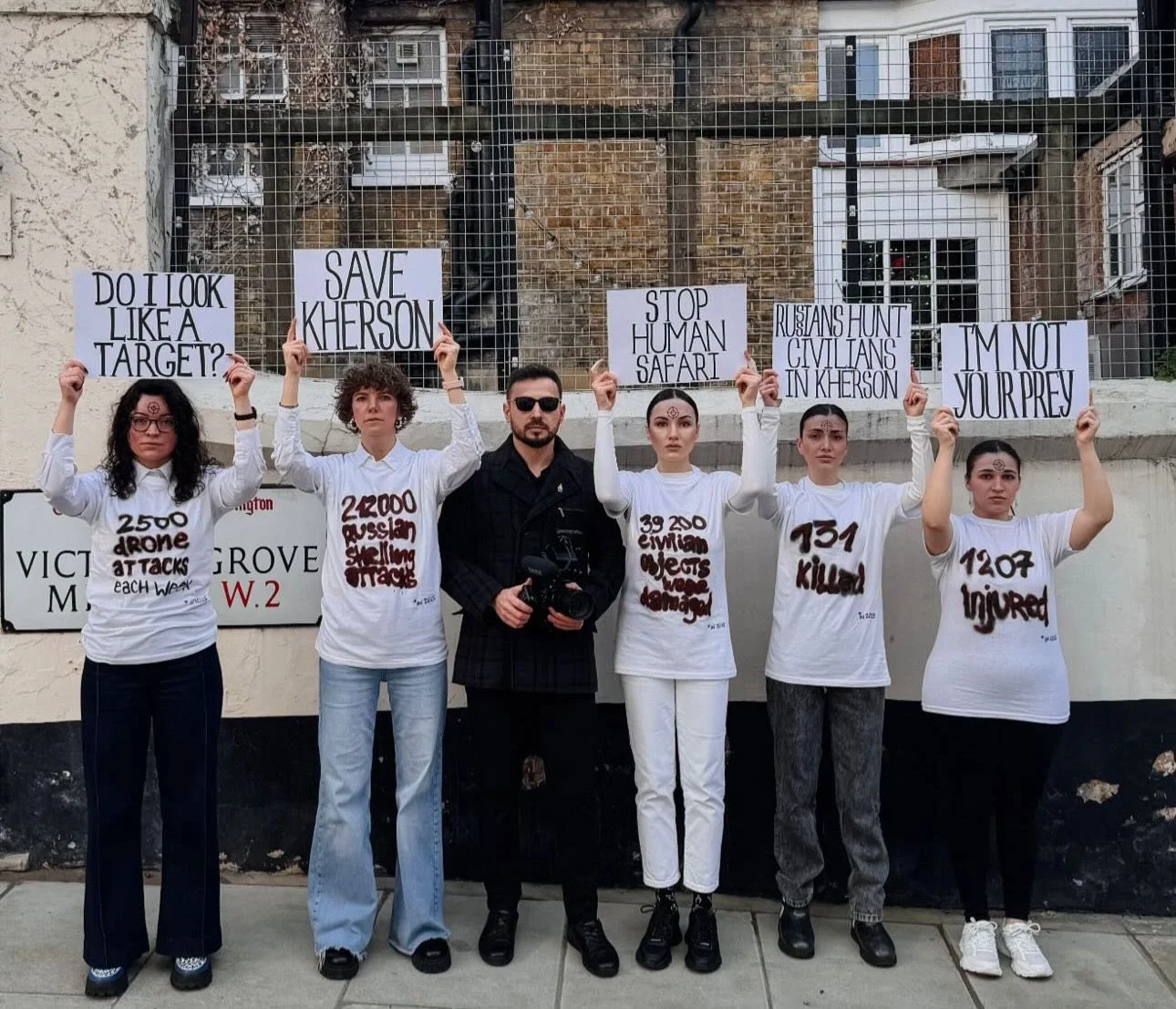

Action of the year: Stop Human Safari

The largest action dedicated to Kherson worldwide was organized by American producer, writer and journalist Zarina Zabriskie, who has been living in Kherson since 2023. In December 2025 she announced a global campaign “Save Kherson / Stop Human Safari”, which took place in various countries on December 13–14.

According to the journalist, the initiative aimed to draw international attention to the shelling of Kherson and to facts of Russian forces using FPV drones to attack civilians. The action involved holding peaceful rallies in different countries around the world.

As a result, about 50 cities in almost 20 countries across six continents joined the international wave of support for Kherson. Actions took place from Norway to Japan, from South Africa to Australia, from Mexico to Bulgaria and the USA. Kherson residents joined the campaign all over the world, the largest action took place in Kyiv.

On December 15 a special screening of the documentary “Kherson: Human Safari” was held at the US Capitol Visitor Center. It took place with the support of US Senators Tammy Baldwin and Roger Wicker and Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur, who acted as co-organizers of the screening.

Obviously, this action did not stop Russian drone attacks on civilians in Kherson and right-bank communities, but no one spoke louder this year about the drone genocide against civilians, including journalists, in Kherson.

Recall that Zarina Zabriskie is the author of the documentary “Kherson: Human Safari”. The film collects the tragic chronicle of the city’s war history – from the invasion and occupation to resistance, liberation, ecocide and the transition to a new terrifying era of drone warfare. The film premiered in June this year.

***

2025 was a difficult, but also encouraging year. Encouraging, because how can one not be hopeful when such people work nearby?

Serhii Nikitenko, regional representative Institute of Mass Information in Kherson region