In Kherson and Donetsk regions, the war has destroyed hospitals, outpatient clinics, and feldsher-midwife stations. Tens of thousands of people were left without access to basic medical care. But in response, mobile medical teams appeared – both from surviving regional hospitals in Ukraine and from international organizations. They come to the most remote villages: examining patients, distributing medicines, providing consultations, and saving lives.

What is the problem?

“Shattered” healthcare

The beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion had a devastating impact on all spheres of life in frontline communities – including healthcare. The occupiers deliberately shelled hospitals and outpatient clinics, trying to deprive civilians of access to medical assistance.

A particularly dire situation is observed in Donetsk region. By February 2022, there were 118 healthcare facilities in operation. Due to hostilities and shelling, 96 of them suffered varying degrees of damage, including 62 secondary and tertiary care institutions and 34 primary healthcare centers. Twenty-five facilities were completely destroyed. In addition, medical colleges in Bakhmut, Kostiantynivka, and Mariupol were partially damaged, according to Volodymyr Kolesnyk, head of the Donetsk Regional Military Administration’s healthcare department, in an interview with Skhidnyi Variant.

Photo: Skhidnyi Variant. Destroyed part of the perinatal center in Kramatorsk after a Russian shelling.

The “doctor–patient” relationship has also been disrupted. Before the full-scale war, the region had uninterrupted internet and mobile coverage, and healthcare institutions were equipped with computers. Now, power and internet outages are common, and patients in remote frontline communities remain without electricity, internet, or mobile connection, unable to contact doctors.

In frontline and recently liberated communities of Kherson region, access to healthcare remains one of the most urgent challenges. People who did not evacuate during occupation or who have returned face a complete lack of basic medical services.

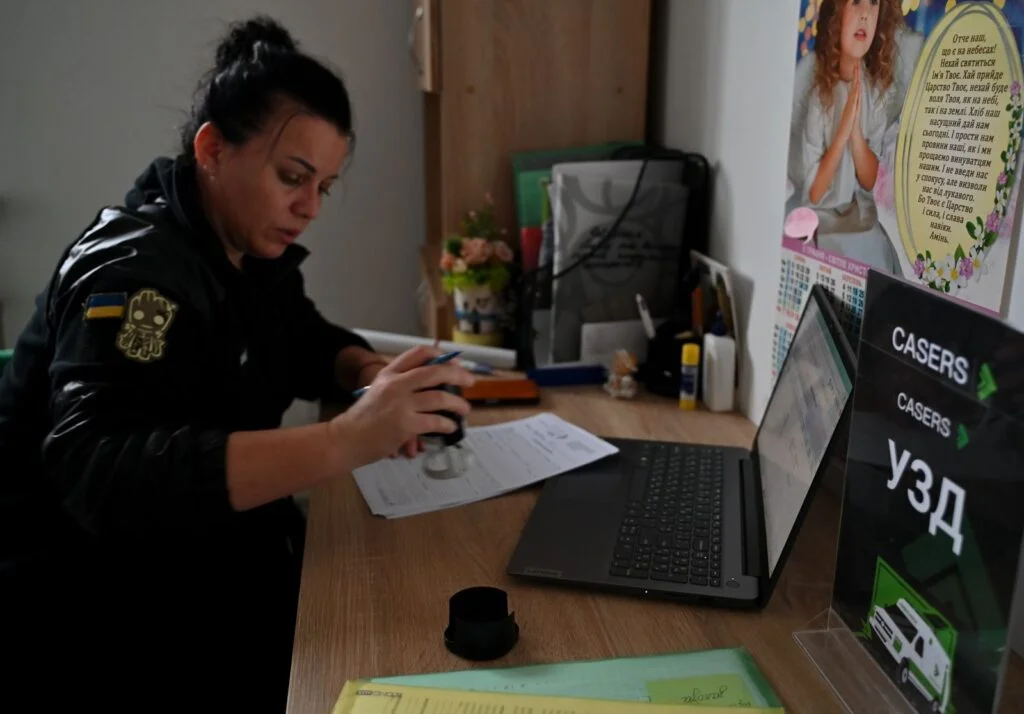

“When I returned to my village, part of Tyahynska community, the first thing I noticed was the total absence of medical care – there was no feldsher, no healthcare workers, no medicines. There weren’t even roads to reach the nearest place where you could buy something for people,” recalls Tetiana Nesterenko, coordinator of mobile medical teams at NGO CASERS.

Photo: NGO CASERS. Tetiana Nesterenko – coordinator of mobile medical teams, NGO CASERS

Many hospitals and outpatient clinics were heavily damaged, roads destroyed or mined, and pharmacies closed. This means residents cannot obtain essential medicines or safely reach regional or district healthcare facilities.

According to the Kherson Regional Military Administration, in liberated right-bank communities, 27 healthcare facilities were destroyed and 117 more damaged. As of September 2025, repair works had been carried out in 57 facilities, restoring full operation in 31 and partial operation in 26.

An equally serious issue is staff shortages: many specialists fled due to danger or lack of work. Those who remain often work under extreme conditions without proper infrastructure. Currently, 677 doctors and 1,547 mid-level medical staff are employed in Kherson region healthcare institutions.

There is a critical shortage of certain specialists, including trauma doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers, particularly pathologists, gastroenterologists, neurologists, endoscopists, oncologists, oncology surgeons, ultrasound specialists, radiologists, hematologists, orthopedic traumatologists, and ophthalmologists.

A key difference between Kherson and eastern regions is the devastated road network, which effectively “cuts off” access to healthcare:

“The first major feature of Kherson is the absence of roads. In the east, roads exist everywhere because those are industrial regions. In Kherson, the key roads run along the riverbank, while other settlements have extremely poor access,” explains Yevhenii Ursalov, head of NGO CASERS.

Due to prolonged stress – first occupation, then over three years of ongoing hostilities – and disrupted treatment routines, the number of complicated cases is growing.

“We are now seeing very critical cases in oncology, endocrinology, and cardiovascular diseases. People are under constant stress and sleep poorly,” says Yevhenii Ursalov.