Kherson’s Ostriv neighborhood hasn’t seen such activity from residents in a long time, such an amount of traffic: cars, minibuses, city passenger buses.

Residents who remained there despite Russian shelling and drone attacks were leaving the neighborhood on their own, and also with the help of the police and Red Cross volunteers.

Since August 2, 2025, Ostriv became even more dangerous and life there even harder. That day a Russian aircraft dropped two guided aerial bombs on the road bridge over the Koshova River, which connects Ostriv to the other part of the city. Only one bomb reached the bridge. It made the first hole in the roadway. The bridge held, and immediately a car drove across it right after the explosion. The next day the Russians dropped five more guided aerial bombs on the bridge. Again only one hit, further damaging the bridge and killing a person.

People are leaving because of the huge threat of the connection between Ostriv and the other part of the city being cut off. Delivering supplies to the neighborhood is already very problematic, and it is possible that soon it will be incredibly difficult to get out of there. Therefore people are trying to evacuate while the damaged bridge can still bear vehicle traffic.

She was the only one left in the stairwell

On all five floors of this stairwell – well-kept houseplants in pots. It seems as if behind the door of every apartment is the life of its residents in all its variety. But in reality the apartments are empty. The residents left: some within Kherson, some far away. More precisely, until the morning of August 5 the apartments in this stairwell were empty except for one.

The occupant of that single until recently inhabited apartment, an elderly woman, looks sadly at the potted plants. She planted and cared for them. And they had been her neighbors for the last year.

“We,” the woman says, “lived here with my husband. He suffered a stroke, was very ill, needed care. He died a year ago. Since then I lived alone. Mostly stayed in the apartment. Only when necessary did I go out to the store. When it was really bad, I went down to the shelter. And during the 2023 flood we stayed here. Volunteers brought us food by boat because the water reached the second floor.”

The sole resident of the stairwell says goodbye to the plants as if to friends who supported her in hard times. She says she hopes a neighbor from another stairwell will look after her charges. The man does not want to leave even in this situation.

Red Cross volunteers help the woman carry bags into the medical minibus, where another woman — a person with a disability who had been taken from her apartment shortly earlier — already sits.

“Because of the bombing there was no gas,” she says. “For four days I couldn’t cook. I lived on bread and water.”

We drive. The hardest part of this short but very nerve-wracking journey is crossing the damaged bridge — slaloming between the holes at the highest possible speed. The car shakes terribly.

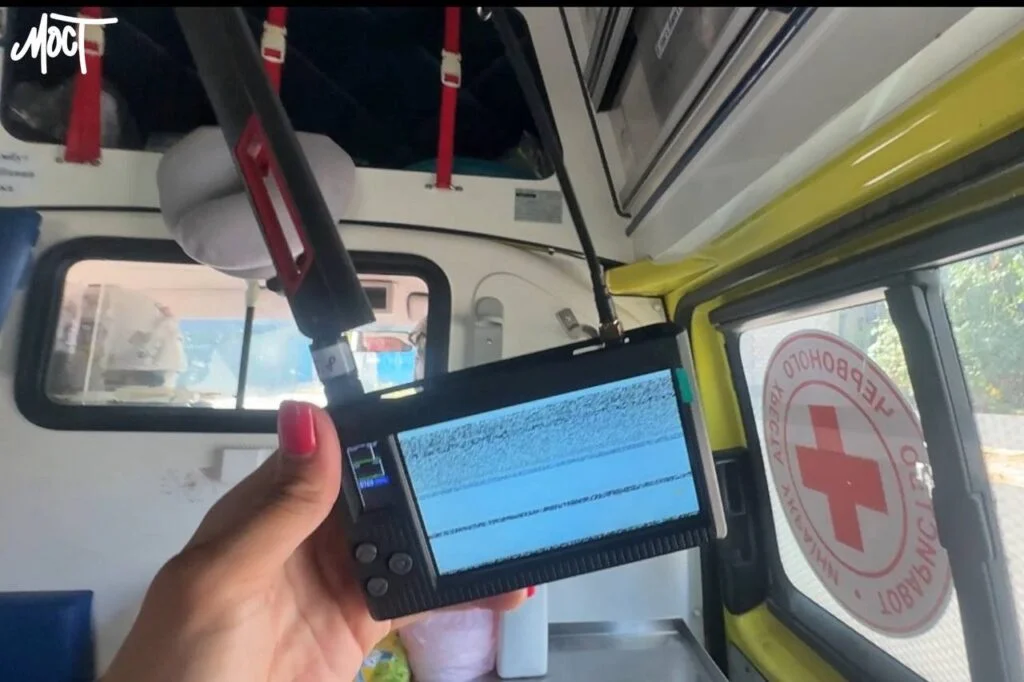

“Everything will be fine,” Red Cross volunteers reassure the women, but their words don’t sound very convincing combined with the alarms from the drone detector.

“The air over the district is clear. People are being given the opportunity to save themselves,” wrote Volodymyr Saldo — the Russian-appointed pseudo-governor of Kherson region — on his Telegram channel on August 4.

But frequent signals from the drone analyzer indicate otherwise: there are Russian drones in the air, and it is possible that they are strike drones capable of hitting evacuation vehicles at any moment.

“We passed the bridge. We’re driving through the city,” the volunteers report. The tension eases somewhat.

We arrive at the temporary accommodation center for evacuees. Here people are helped to process internally displaced person documents and are given humanitarian aid (water and food packages).

A doctor is available and medical assistance can be received.

From here a new stage in these people’s lives begins. Some already know where they will go. Some are waiting for the resettlement assistance promised by the local authorities. But for the evacuated “Ostriv residents” the present uncertainty is still better than the certainty that would await them if they had stayed home.

“You are people of steel”

A middle-aged man, saying “Thank you, you are people of steel,” shakes the hand of a police officer who helped him and his parents leave Ostriv with his right hand. With his left hand the man holds a black cat with a necklace close to him.

“This is Tonka,” he says, “our little miracle. I am very grateful to the 201st patrol police crew. They evacuated us. I was very afraid for my parents. They are almost 80, don’t walk well. I worried about how we would manage in such a situation. We called the police, the guys came and did everything.”

This family has somewhere to wait out the hard times: one of the elderly couple’s sons lives in the relatively safe Tavriysky neighborhood of Kherson.

Vasyl Yakymovych was also evacuated from Ostriv by police officers. Next to him in the car are a few hastily packed bags with belongings.

“Because of health problems,” the elderly man says, “I have trouble walking. But the guys were great, they helped me.”

The pensioner says that his granddaughter — the only relative he has left — will take him in.

On the bus

Residents of the neighborhood who can take care of themselves were transported on passenger buses that were temporarily taken out of service.

At the collection point, MOST reporters spoke with several neighborhood residents.

“I hesitated for about three days,” says the woman who introduced herself as Lyubov, “and finally decided to go. We lived here when electricity and gas were supplied intermittently. But if the bridge is destroyed and Ostriv is cut off from the city, it will be completely unbearable. And in general it’s very hard to leave here. Very…”.

The woman cannot continue, she begins to cry.

“I,” says another woman, Lidiya Mykhailivna, “will live at work — in the hospital. The administration doesn’t object, they will allocate me a place for temporary accommodation. I hope this won’t be for too long. I want to return as soon as possible. After all, I have lived on Ostriv since 1971. I love this neighborhood.”

“My daughter,” says another Ostriv resident, Halyna Oleksiivna, “lives in Germany, but I don’t want to go there. What would I do there? I don’t want to leave Ukraine. Where would I live? I don’t know yet. Wherever they offer.”

Mykola Taranenko, commander of the Kherson regional rapid response unit of the Ukrainian Red Cross Society, says that the vast majority of people evacuating from Ostriv are pensioners.

“Many of those evacuating,” Mykola says, “are low-mobility people; they absolutely cannot stay there. People react differently. Some cry, mourn. Some thank us for helping. Someone just kissed me.”

On the bus, because of its size, it shakes less than the Red Cross medical vehicle, but that doesn’t make it calmer. On one of the seats a woman holds a black-and-white English setter to her chest, trying to calm the nervous pet.

“How did we live? We lived in ways you can’t tell or write about,” she replies with bitter irony when asked about life in one of Kherson’s most dangerous places.

On one of the seats is an older man. He says this is his second trip to Ostriv — he went for another load of things — warm clothes, because he’s not sure he’ll be able to return home before it gets cold.

On a nearby seat sits a woman of retirement age. She says that she lived in Poland for a year but had to return because she needed to care for her seriously ill son.

“The biggest problem on Ostriv,” she says about her life in the neighborhood, “was the lack of a pharmacy. When the Nova Poshta branch worked, people placed online orders, but that’s an extra cost for delivery. For an average pensioner that’s a problem.”

According to the Kherson Regional Military Administration, as of 15:00, 547 residents have been evacuated from the Korabel neighborhood (the official name of Ostriv). Among them are 46 children and 45 low-mobility people. At the time of the strike on the bridge there were about 1,800 residents remaining in the neighborhood. Currently the area has no gas supply, but there is electricity and water. Evacuees are given full support — they are helped to reach relatives or temporarily accommodated in shelters or evacuated to other regions.