On the third anniversary of Kherson’s liberation we again hear odd formulations “when the Russians left Kherson”, “after the Russians’ withdrawal”. In reality, the Russians were driven out of all advantageous lines they had captured in spring 2022, and they fled from the right bank of Kherson region. At the price of the blood and sweat of Ukrainian warriors, a highly complex operation was carried out that has already entered history.

Prerequisites of the counteroffensive

At the beginning of July Russia controlled 95% of Kherson and 10% of Mykolaiv regions. At the end of May Russian officials approved plans to annex the occupied regions, including Kherson. The Russian occupation authorities in the region planned to hold a referendum on joining Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions by the end of 2022, while the occupied parts of Mykolaiv region (Kinburn Spit and Snihurivka district were to be included into Kherson region, but soon officials postponed the date to autumn – according to British intelligence representatives, amid fears that the territories would be recaptured by the Ukrainian army.

By March 11 the Russian offensive on many fronts in Mykolaiv region had stalled, prompting a gradual retreat by the end of the month. Some Russian forces that failed to enter Voznesensk and Bashtanka were redeployed toward the Davydiv Brid direction. Local residents report that a huge column of thousands of vehicles and armored vehicles moved along the road from Snihurivka to Velyka Oleksandrivka.

At that time Ukrainian forces attacked them with artillery. On the road from Kalynivske to Davydov Brod in spring 2023 dozens of destroyed Russian vehicles still stood, and the craters on the road were patched only at the end of 2023. Those patches are still visible there.

On March 30 Ukrainian forces regained control of the settlements Orlove, Zahradivka and Kochubeivka.

On April 6 the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine reported that during the offensive Ukrainian forces had driven the Russians out of the settlements Dobryanka, Novovoznesenske and Trudolyubivka, and later that day – about the liberation of the village Osokorivka.

At this point the front for a while fixed itself along the road from Nezlamne (Potemkinske) to the Watermelon Monument. Trenches in the groves are visible there to this day, and burned-out armored vehicles remained in the groves until the beginning of summer 2023.

On April 18 Russian troops together with formations of the so-called “DNR” and “LNR” launched a large-scale offensive in Donbas. To do this the enemy was forced to redeploy part of its forces from the southern direction to the east. Units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine took advantage of this, conducting a number of successful operations and liberating several fortified enemy positions along the southern bank of the Inhulets River.

As of June 1 the Institute for the Study of War reported that Ukrainian counterattacks in Kherson region had successfully achieved their objectives and disrupted Russian ground supply lines along the Inhulets River. During June Ukrainian units liberated a number of territories in the northwest of Kherson region. The fiercest fighting took place around Davydiv Brod. Despite some successes, the main line of Russian defense remained in place. By July 9 Ukrainian forces had carried out a series of local counterattacks, forcing the enemy to go on the defensive and fortify their positions.

Those positions are still visible. Along the Inhulets River, in the groves and around settlements. The Russians dug in equipment right in people’s yards, for example, in the village of Bilohirka.

At the beginning of July Ukrainian authorities, including Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories Iryna Vereshchuk, began appealing to residents of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions to evacuate due to a planned counteroffensive by the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Citizens who remained in the temporarily occupied territories, including in Kherson, were urged to set up shelters and prepare for active combat. Vereshchuk warned that intense fighting and shelling were expected in the coming days, emphasizing: “The AFU is advancing”.

On July 9, 2022 President Volodymyr Zelensky gave orders to Ukrainian troops, including forces of Operational Command “South”, to begin liberating the occupied territories. Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov confirmed that Ukraine was forming a powerful grouping to conduct offensive actions.

Fighting on the Mykolaiv direction

When people talk about the Kherson counteroffensive, they very often forget the sector we conditionally call the Mykolaiv direction. These are the steppes between the Dnipro-Buh estuary and Snihurivka.

Here the enemy held out in large settlements like Oleksandrivka, Pravdyne, Posad-Pokrovske and others. And the intensity of the fighting there was no less, and at times much greater than in the Davydiv Brod area. Ukrainian fighters attacked Pravdyne and Posad-Pokrovske repeatedly in spring and summer 2022. At that time they were only able to retake the ruins of the latter village. Positions ran along its southern borders, along the canal line.

Russian positions ran two kilometers along the line of another canal. The enemy used its concrete slabs as fortifications. This canal runs from Blahodatne to Pravdyne.

Last year my colleagues and I worked with sappers of the 808th brigade right in the area of these positions. Around there, except for sparse groves, there was no shelter at all, so it was very advantageous for the Russians to hold those positions.

The 28th Separate Mechanized Brigade and the 241st, 124th and 126th Territorial Defense brigades advanced here. A bit further north, toward Snihurivka, advanced the 121st Territorial Defense brigade, the 59th and 63rd brigades and the 17th Tank Brigade.

Ukrainian forces attacked the Russians, but could not push them further.

All spring 2022 the AFU attacked the airport near Chornobaivka and its surroundings. This constrained the Russian army’s actions and knocked out a large amount of their equipment and ammunition.

The beginning

In the well-known video, which is still the most comprehensive analysis of the AFU’s offensive in Kherson region, it is stated that the counteroffensive began at the end of August with strikes from HIMARS on Russian headquarters and depots.

In reality, the first HIMARS strikes on Kherson began a little earlier.

The morning of July 10 began for Kherson residents with the sounds of explosions. At 5 a.m. three powerful explosions were heard and another three explosions – around 10:30 a.m.

At the time we did not understand what was happening, and I think we were not the only ones.

In local public groups Kherson residents wrote that a strike was carried out on the territory of the military unit on Pestel Street in central Kherson. Russian troops were stationed there.

A few days later it became known that during the strike the commander of the Russian 20th division, Colonel Oleksii Horobets, was killed. Along with him, several dozen officers died.

The deputy commander of the division – chief of staff Colonel Serhii Kens was also unlucky.

Russian social networks reported that Kens could not be delivered to the hospital in time.

According to intelligence data, the deputy commander of the division for military-political work Oleksii Avramchenko and the deputy commander of the division Kanat Mukatov also did not survive that Sunday morning in Kherson.

The cunning of the operation was that the strike occurred during the morning formation of Russian soldiers with participation of junior commanders. A few hours later a delegation of the division’s leadership arrived at the site, which became known to Ukrainian military. At 10:30 another strike was carried out, which killed the senior leadership of the division.

Later there would be dozens of strikes on the Antonivskyi Bridge and the bridge at the Kakhovka HPP, but this first HIMARS strike sowed panic among the Russians.

On July 11 the Ukrainian army reported that it had retaken the village Ivanivka of the Vysokopillia community. This village is located between Arkhanhelske and Vysokopillia. On July 27, 2022 Ukrainian forces announced that they had restored control over the villages Lozove and Andriivka, both on the eastern bank of the Inhulets River. The village Lozove had disappeared even before 2022. There was not a single house there, so it would be more accurate to say that the Ukrainians regained the area of the former village.

We wrote about the fighting in Andriivka in a separate piece, relying on testimony from local residents. They claim that Ukrainian warriors recaptured the village on July 21. On that day they began to be ferried across the river, and the village turned into hell on earth.

The 35th Marine Brigade entered the village. How the marines did this remains a mystery to us. Part of Andriivka is on a cliff and the Russians holding that height saw the Ukrainians as if on a palm. This is visible in the photo.

Later Sergeant Burlaka recalled that the Russians concentrated a lot of equipment and artillery on this sector, which nevertheless could not wipe out the Inhulets bridgehead that connected to the other bank by pontoon crossings. These crossings were also attacked with all types of weapons. Rocket stages and large fragments of aerial bombs still lie on the territory of Andriivka. The village disappeared after the summer battles.

The target of the marines and other units was Sukhy Stavok — a village reached from Andriivka by a straight country road.

An asphalt road ran between the villages, hidden on both sides by groves. The main battles unfolded here. More than 3 years have passed since then, but the groves have not recovered and the charred dry trunks still stick out.

Here the 35th destroyed almost the entire 109th regiment of the “DPR” and advanced toward Sukhy Stavok.

In the north Ukrainian warriors could not cross the Inhulets in the Davydiv Brod area, which was held by Russian paratroopers, but Chechen volunteers and attached units had success and drove them out of Arkhanhelske.

The village is partly located in a lowland, so the Russians simply retreated to the ArcelorMittal quarries and took up positions there. Those positions were maximally fortified, and the Russians hid from shelling in sea containers buried in the ground. There was enough construction machinery at the quarry.

Control over Arkhanhelske had strategic significance, as the more or less passable road to Vysokopillia passed through here, which the Russians had turned into a key defensive point.

On September 4 Vysokopillia fell. According to locals, the fighting there was fierce. We ourselves saw this when we arrived in the settlement a week after its liberation. The AFU concentrated a firestorm on the hospital, which towered above the settlement, the railway station area and the depots. In the depots it was possible to burn hidden equipment: BMPs and BMDs of Russian forces. Near one of these BMDs I found a burnt Azerbaijani coin. Most likely, these units arrived in Kherson region from Karabakh.

At the same time the AFU took Ternovi Pody on the Mykolaiv direction and advanced toward Kyselivka. But the Russians launched a counteroffensive and retook Ternovi Pody.

Marines and fighters of the 17th Separate Heavy Mechanized Brigade meanwhile took Sukhy Stavok. Later the Russians were pushed out of the steppe Kostromka as well. The AFU’s goal was clear — to reach Bruskyne, which stands on the Davydiv Brid–Beryslav road. But they failed to do so.

At this time the AFU concentrated on weakening the Russians’ logistics, striking three bridge crossings on the Dnipro. For a time the bridge over the Kakhovka HPP locks was put out of action and the Antonivskyi road bridge was heavily damaged.

On September 6 the 128th brigade liberated Novovoznesenske. This small village is located on the road to Novovoronovka.

At the same time a Russian attack began on a small bridgehead in the area of Blahodativka–Novohrednove–Mala Seydemenukha. Ukrainian warriors had entered the villages back in summer, but heavy fighting here began in early September when Russian troops realized that expanding the bridgehead could split their defense in half.

Second stage. Offensive on the Watermelon

On September 6 the AFU launched an offensive in Kharkiv region, forcing the Russians to hastily redeploy their combat-ready units from the Kherson front to the Kharkiv front.

On September 9 fighters of the 46th Separate Airborne Assault Brigade entrenched in Blahodativka and expanded the bridgehead near Bilohirka.

On September 12 soldiers of the 128th Mountain Assault Brigade after heavy fighting liberated Myroliubivka, cutting the road. In the Blahodativka area marines and paratroopers expanded the bridgehead, finally taking Mala Seydemenukha and Bezimenne.

On September 14 the Russians struck Kryvyi Rih with “Kinzhal” missiles, destroying the dam of the local reservoir. The Russians’ intent was to hinder Ukrainian troops from establishing crossings and possibly destroy those already in existence. However the plan failed. The author arrived in Kryvyi Rih early on the morning of September 15, when the yard of the hotel where they stayed with colleagues was flooded, and trucks were busily hauling slag and earth to fill the dam. By the evening of September 15 the water receded, meaning the downstream flow did not cause major disaster.

At this moment the Ukrainian offensive in the Sukhy Stavok area falters due to enemy helicopters, minefields and artillery. By October 1 neither side was advancing significantly. Heavy fighting raged in Bezimenne — the Mykolaiv village that jutted as a wedge into Kherson region. During these battles the village ceased to exist

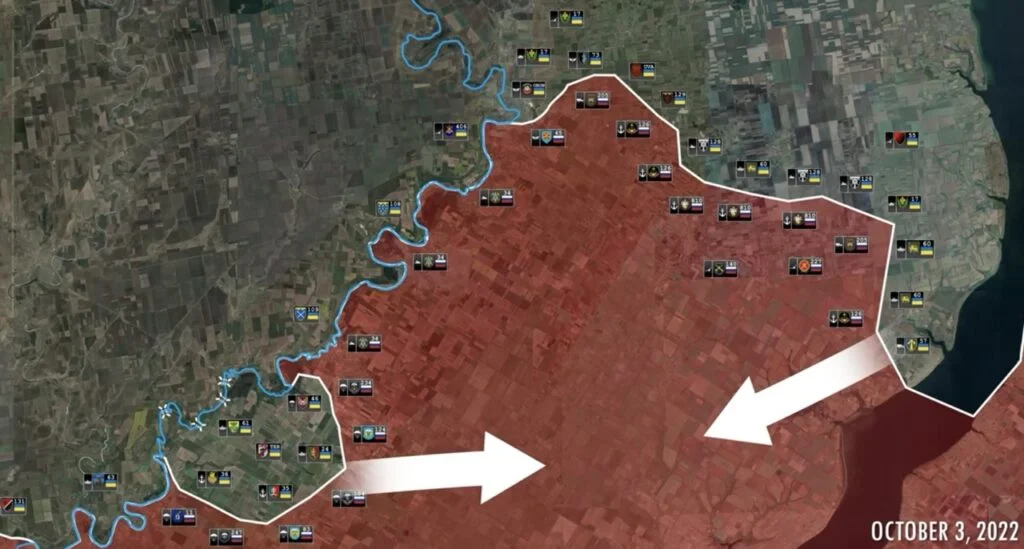

On the night of October 1 regrouped forces with about 100 tanks and BMPs begin a massive offensive along the Dnipro toward Novooleksandrivka and the community’s villages. Fighters of the 57th, 60th Motorized and 17th Tank Brigades entered unprepared Russian positions. Here the AFU crushed the elite 10th Separate Spetsnaz Brigade of the RF.

At the same time the 128th Mountain Assault Brigade entered Khreshchenivka and Zolota Balka.

By October 3 the AFU liberated all the Dnipro villages of the Novooleksandrivka community. The Ukrainian command’s plan was clear: to break through the defense in the Bruskyne area and connect with units in the south, encircling the Russian grouping.

At this point the Russians began to panic, exacerbated by the lack of reserves that could not be quickly transferred across the Dnipro. They began to flee, abandoning equipment, killed and wounded.

By the morning of October 4 Ukrainians liberated part of Dudchany and the steppe villages to their north. Taking Dudchany completely was impossible because the Russians blew up the bridge over the ravine.

But the breakthrough forced the Russian army to flee from Davydiv Brod, Velyka Oleksandrivka and surrounding villages. The Russians also fled from the steppe villages Bilyaivka and Petropavlivka.

On October 5 the front line partially stabilised and the offensive seemed to slow down, but the next day AFU fighters crossed the bridge in Dudchany and drove the Russians out of the village.

On October 9 the Russians tried to retake Nova Kamianka, but unsuccessfully — losses in equipment and manpower took their toll.

The Russians’ flight from Kherson

The next month saw mostly positional fighting. The Russians repeatedly declared that they were turning Kherson into a fortress that they would hold at any cost, but MOST correspondents and readers did not confirm this information.

Only marginal local collaborators were saying that Kherson would not be surrendered, while at the same time the Russians were already beginning evacuation from the right bank. They announced evacuation of their institutions and organisations, removing property, museum valuables and archives.

At the same time they transported any willing residents of Kherson. Tens of thousands of people were ferried to the left bank, and soon Kherson residents noticed that Russians were no longer in the city.

On November 9 Shoigu issued the well-known order for “regroupment”.

“We learned that the enemy had retreated as we advanced through territories that only yesterday were not under our control, so it wasn’t a piece of news from the internet after which we’d be like ‘oh okay, let’s go to the center for photos’,” recalls the commander of the combined unit Buzkyi Hord Ilya Zelinsky.

The guys had been fighting on the Kherson direction for all nine months and know better than anyone how difficult the battle for Kherson was.

“The final stage of this task began for us on November 8 and ended on November 12 with reaching a new line and switching to defense. Of course, the commander of the RTG (company-tactical group, – MOST), in which we were, informed us every day after the final transition to the attack about the enemy’s presence. On the 8th he was still on the front edge,” Ilya remembers.

59th Brigade fighter Pavlo Petrychenko, according to his own words, realized that the Russians had retreated a day before November 11 – the date officially considered the day of Kherson’s liberation.

“We were then driving to a position – on the border of Mykolaiv and Kherson regions – and came under ‘Grad’ fire. At that moment we realized it was a covering barrage. The Russians left their artillery to cover the withdrawal of their troops”, he recalled in 2023.

“Having withdrawn,” Pavlo and his comrades returned to replace damaged equipment and report to headquarters.

“Guys, we said, we need to go work, because there is information that the f…kers have left. We returned to the position – and already along the front edge it became clear that there were no Russians there. In the trenches there were only dummies and scarecrows – things that created the effect of their soldiers’ presence”, our interlocutor recounted.

Pavlo died on April 15, 2024 in Donetsk region.

Later media began to claim that the US forced the AFU to allow a peaceful retreat of the 30,000-strong Russian grouping from Kherson. This is asserted by Bob Woodward after conversations with US officials in the book “War” (Woodward Bob: War).

The author writes that when the Ukrainian army was liberating Kherson in autumn 2022, US intelligence warned that the risk of a nuclear strike would increase if the Russians suffered major losses during the withdrawal from the city.

According to the Ukrainian army’s plan, the AFU were supposed to pursue the retreating Russians and deliver massive strikes, but this did not happen – the Russians retreated without significant losses.

It turned out that before the withdrawal Joe Biden received a warning that an AFU strike on Russia could lead to a 50% probability of a nuclear strike by Putin.

The Americans called the Chief of the General Staff of the RF Armed Forces Valery Gerasimov, who promised the US Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley that in the event of large losses during the withdrawal from Kherson nuclear weapons would be used.

After this the Russians received a kind of security guarantee and moved to the left bank, ferrying all their equipment and personnel across.

MOST journalist Marharyta Dotsenko, who was in Kherson at that time, claims that shelling of the crossing near the Antonivskyi Bridge lasted all night. And the AFU were certainly catching up with those who were retreating.

And although the Russians managed to get some equipment across the bridge by covering the HIMARS-made holes with thick metal sheets, the AFU captured a large amount of trophies near Kherson in the form of abandoned equipment and ammunition.

The withdrawal from Kherson became one of Russia’s greatest military failures since the start of the invasion, leading to demoralization of personnel and the loss of the only regional center of Ukraine that it had managed to capture. However, the troops that were withdrawn from the right bank of Kherson region allowed the Russians to launch an offensive in Donbas.

Kherson celebrated, carrying Ukrainian soldiers on their shoulders, and perhaps not all citizens realized that the city would soon have to go through hardship. But in any case, the heroism and sacrifice of Ukrainian warriors are certainly something all Kherson residents should remember.