We went to see the work of a unique laboratory where fighters of the 3rd battalion of the 40th separate coastal defense brigade of the 30th Marine Corps of the Naval Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine refine and improve drones, but ended up at a real combat operation on the islands. It cannot be shown, but the military allowed us to tell what we saw.

The place where they adjust the work of drones and company-level combat resembles something between a TV channel control room and a computer club from the early 2000s somewhere in the neighborhood. Except the video shot here is specific and they don’t play games.

“Drones are important at the front, but people are even more important. No drone, even the best in the world, can capture a position. After drones, a person still has to go in. A living person who goes in will clear the position and consolidate it,” – says the battalion commander

He is a tanker whom fate moved from the Donbas fields, which he had driven all over in a tank, to the Kherson marshes. Before the war, neither he nor most of his subordinates had often seen so much water at once. The battalion holds difficult sections of Kherson region, and attacks even more difficult ones — the islands.

A tank, like other heavy equipment, won’t help here, so the marines are supported by artillery and drones.

We were supposed to talk about drones, but the tense atmosphere and slight commotion hint that there will be no time to talk for now.

“We’ll fight now,” – says the commander and gets on the line with his subordinates. He controls a large military organism, and at the same time commands the infantry, directs drones, calls in artillery strikes and does dozens of other small, sometimes incomprehensible tasks.

On the screens we see fragments of painfully familiar islands. Broken dachas, wrecked piers and “little bridges.” I try to recognize which islands these are and explain to the press officer from Odesa what Kherson dachas are and why all the islands below Kherson are built up.

Meanwhile the commander orders all drones to be launched. His gaze is focused on one of the large screens. There, in a relatively substantial, for the marshes, building, the Russians are entrenched. Two of them, according to the commander, have already been destroyed today. “There are 4–6 left, no more.”

From the story we understand that fights on this patch have been going on for a long time, because somewhere nearby are our positions held by marines. Today they have to storm this building, but first drones are working here.

One FPV was supposed to get into a hole in the wall, but it fell without detonating; the serviceman in front of the screen quietly says “fuck”, which a few people repeat, and orders the UAV operators to fly there. On the neighboring screen we see the marshes starting to catch fire. Who set them alight is unclear, but clearly it is one of the methods of cover. Infantry will hardly get through a wall of fire, and if they do, they will find themselves in a black desert where hiding will be impossible.

The commander meanwhile watches the screen closely. There are just marshes, but he sees our fighters preparing for the assault. No matter how intently I look, I see nothing. But I root for them and ask about motivation.

“People’s motivation is different. Some have relatives on the left bank, some in Crimea,” – says the commander, adding, “actually, war on the islands is very hard. Look, they sit there and have nowhere to retreat, we would smash their boats. They sometimes sit there without food and water,” – says the commander.

He tells how they recently watched a “Buryat” who ran from that very building to the river for water.

“He runs out, looks around to see there are no drones, and we had pulled the drones back, but we still see everything. He runs out, drinks and runs away, here they have a burrow,” – he points to some bushes, – “and here’s a burrow,” the serviceman recalls.

That “Buryat” is no longer alive, but shallow burrows dug on a sediment island can hide someone else.

According to the military, the Russians contacted their command and reported problems. They clearly understand that Ukrainian soldiers will storm them. Intensive artillery strikes and drones do not bode well.

The commander explains the plan. Indeed, nothing good awaits the Russians here.

Buildings where the Russians are holed up begin to be hit. FPV drones increasingly hit structures, and artillery is also working. White and black smoke, in large plumes, spreads from the “patch” held by the Russians.

We continue the conversation as we prepare to leave. We will not be able to watch the rest of the operation, because we need to go to the laboratory for which we came.

The commander answers our naive questions while watching the battlefield on the TV hanging on the wall.

“They have no hope, do they?” – asks my foreign colleague, who is also following what is happening on the screen.

“We have no other choice but to go forward,” – replies the commander.

Meanwhile on the screen we see new explosions, buildings gradually change shape, melting in the spring sun, but the Russians do not run out. They are afraid of drones.

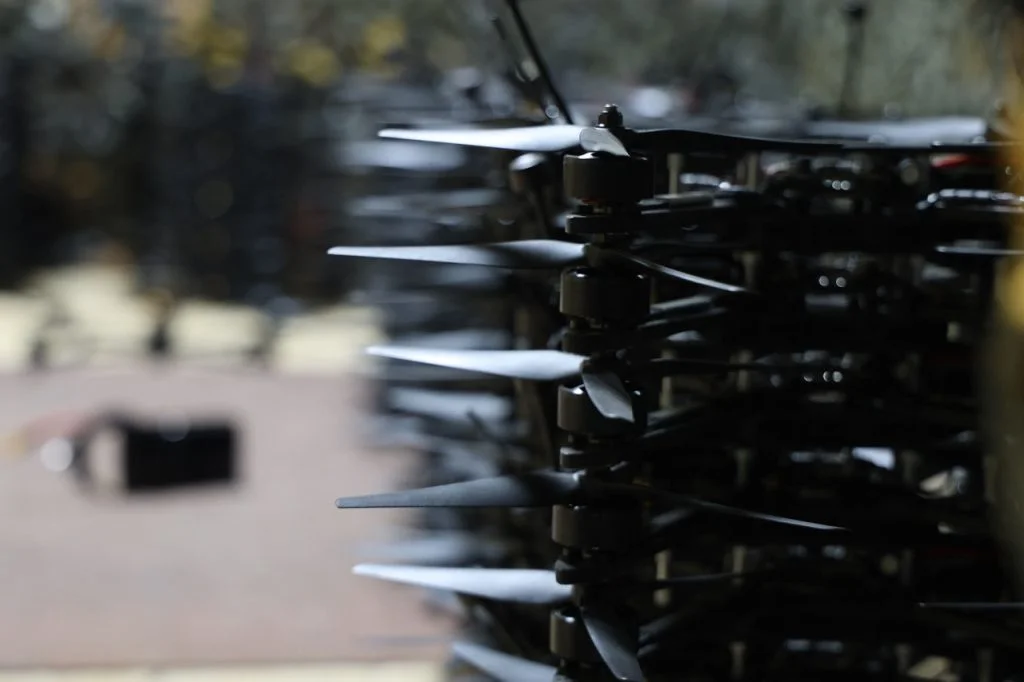

It is obvious that the drones, for which we came to the battalion, are used here in large volumes.

Soon the commander orders us to get ready. Despite the fact that fighting continues on the island, the military decide to move us from the location while the sky is still clear.

On the way the commander listens intently to a live feed on his phone. We hear nothing, but from his behavior it’s clear that everything is going according to plan. Or at least I want to believe so. I want those Russians sitting in those semi-ruined buildings to be killed today. We used to pass by them dozens of times by boat “Crimea” on the way to my aunt’s dacha about 30 years ago.

The laboratory, which the soldiers themselves call the “Drone Workshop”, greets us with a light aroma of food. The cook skillfully chops something and barely pays us any attention. It’s clear he’s in a hurry.

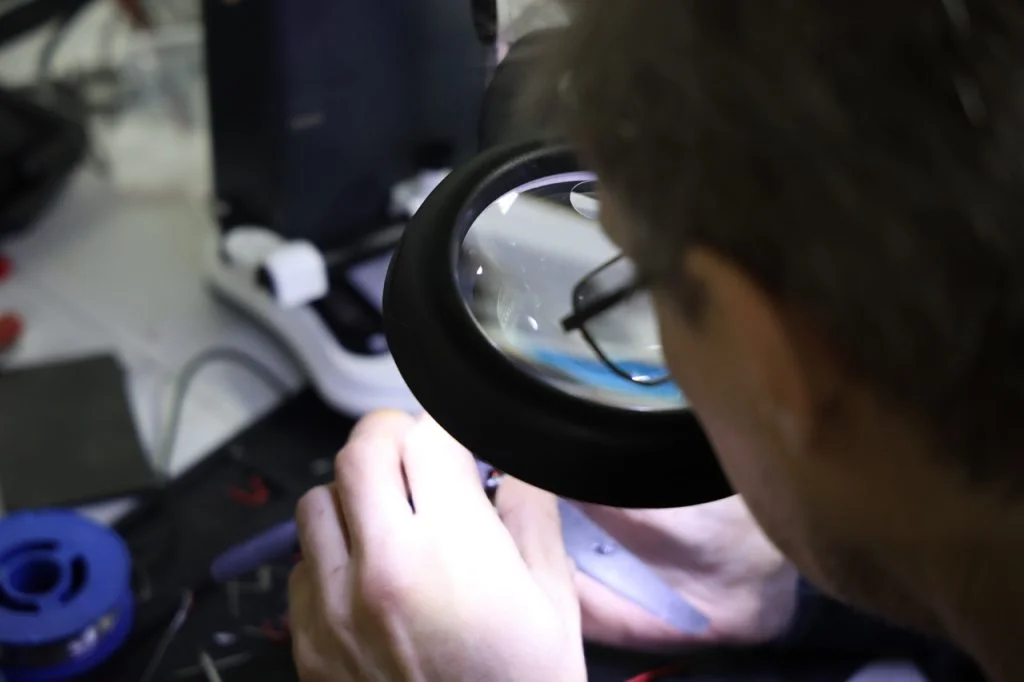

The workshop is run by a fighter with the call sign “Zidan”. Before mobilization he was a programmer. He says his professional skills are very useful now. He and his comrades set up the workshop themselves. In the main room three people work on the drones. Someone solders parts, someone programs or tests drones.

It turns out drones do not always arrive to the troops fully ready for use. That is why the battalion command created this workshop-laboratory.

According to “Zidan”, receiving a new drone for setup and refinement takes from two to three hours. Then, once they get the hang of it, they spend no more than 10–15 minutes per drone.

“These are 13-inch drones (drone size 13 inches, – MOST) — they arrived to us completely disassembled. We soldered them up, assembled them. We work constantly,” – says Zidan.

While we walk around like in a museum, the guys assemble and program the next drone.

The head of the laboratory dreams of expanding the workshop — for example he wants equipment that would allow them to assemble battery packs themselves.

“It would be both faster and cheaper. Sometimes you have to wait a very long time until certain batteries arrive. We would assemble faster,” he says.

The guys working in the laboratory are almost all mobilized. Some, like “Chyzh”, fought in the marines since 2022, and some joined the brigade, like “Zidan”, one and a half years ago when the brigade was first formed.

In the adjoining room hammers are pounding — the fighters are setting up another workspace. It will be a small shop with 3D printers. Two are already working, printing spare parts or even a casing for a munition. A few more are waiting. In total the shop will have 8 printers.

Nearby drones of all sizes and modifications lie in neat rows. They are almost ready for their first and last combat flight. But before that they must be tested on the training ground.

The laboratory can prepare about 100 drones for operation per day.

Average daily consumption in the battalion is not publicized, but 150 drones were prepared for today’s operation. Whether they will use them all — nobody knows.

As a rule, all innovative solutions are immediately distributed at the brigade level, and later to neighboring brigades.

The commander does not join the conversation, but it is clear he is proud of the laboratory. He businesslike asks the press officer whether there is anything similar in neighboring battalions? Judging by their quiet talk in the corner, this is the best.

Obviously, all this equipment costs a lot. Expenses are partly covered by volunteers and partly by fighters buying with their own money.

Most of the drones are sent by Ukrainians in the Czech Republic.

“They are very strong volunteers. They supply drones to Madyar and Kyrylo Kyrylovych Veres. And they help us a lot,” – says the commander.

While “Zidan” shows his workshop, the commander immerses himself in his phone.

“They entered the positions, they are clearing,” – he says quietly.

He does not show the video, but it is clear that on the island we recently saw on the screen a fierce battle is now underway, in which such drones as we see now play a major role.

Soon the commander says goodbye and goes to lead the battle, and we pack up as well.

On the way out we peek into the kitchen where Vasyl, a former chef of the famous Lviv restaurant “Hrushivskyi”, has finished cooking pea soup with smoked ribs and croutons. He smiles sincerely and prepares to feed his engineers.

The sun is shining brightly outside, somewhere far on the islands the reeds are burning, and a breeze drives black ash over the ground.

Friends, fighters of the 3rd battalion of the 40th brigade constantly need help, so we urge you, if possible, to support the defenders of Kherson region. The money will be used for the needs of the drone laboratory, about the work of which you learned today

🔗Link to the jar

https://send.monobank.ua/jar/2YrQ54EHED

💳Bank card number

4441 1111 2155 2636